“We really haven’t seen a monumental change,” said Mary Bugbee, health care research director for the Private Equity Stakeholders Project, a watchdog group based in Chicago. “Legislators have a lot to say, but at the end of the day there’s isn’t enough willpower and appetite to actually do something. It’s a huge failure.”

Elected officials said they’re still pressing to give regulators stronger tools to scrutinize buyouts of hospitals, nursing homes, and other health care assets. Some want to restrict private equity practices such as sale-leasebacks, in which firms sell hospital property and then pay rent to landlords, and dividend recapitalization, in which firms borrow money to pay cash dividends to shareholders.

Until new laws are in place, regulators have no basis to challenge health care buyouts. “Steward is a worst-case example of what can happen,” Bugbee said. “But the strategies Steward employed are used at other hospitals and nursing homes.”

Private equity representatives say the bills in Congress and state legislatures unfairly target their industry, contending its role in health care is limited. They cite data showing private equity invests in just 8 percent of US hospitals and owns less than 4 percent of health care providers.

“American companies, in health care and other economic sectors, need more investment from all sources,” Drew Maloney, president of the American Investment Council, a trade group, wrote to the US Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions in September. “Private equity and private credit can provide the needed capital.”

Private equity firm Kinderhook Industries’ purchase of Stewardship Health, a Steward affiliate that managed the company’s primary care doctors and other clinician, was completed Oct. 31. The transaction laid bare the mismatch between fast-moving Wall Street dealmakers and the government players working at a glacial pace to regulate them.

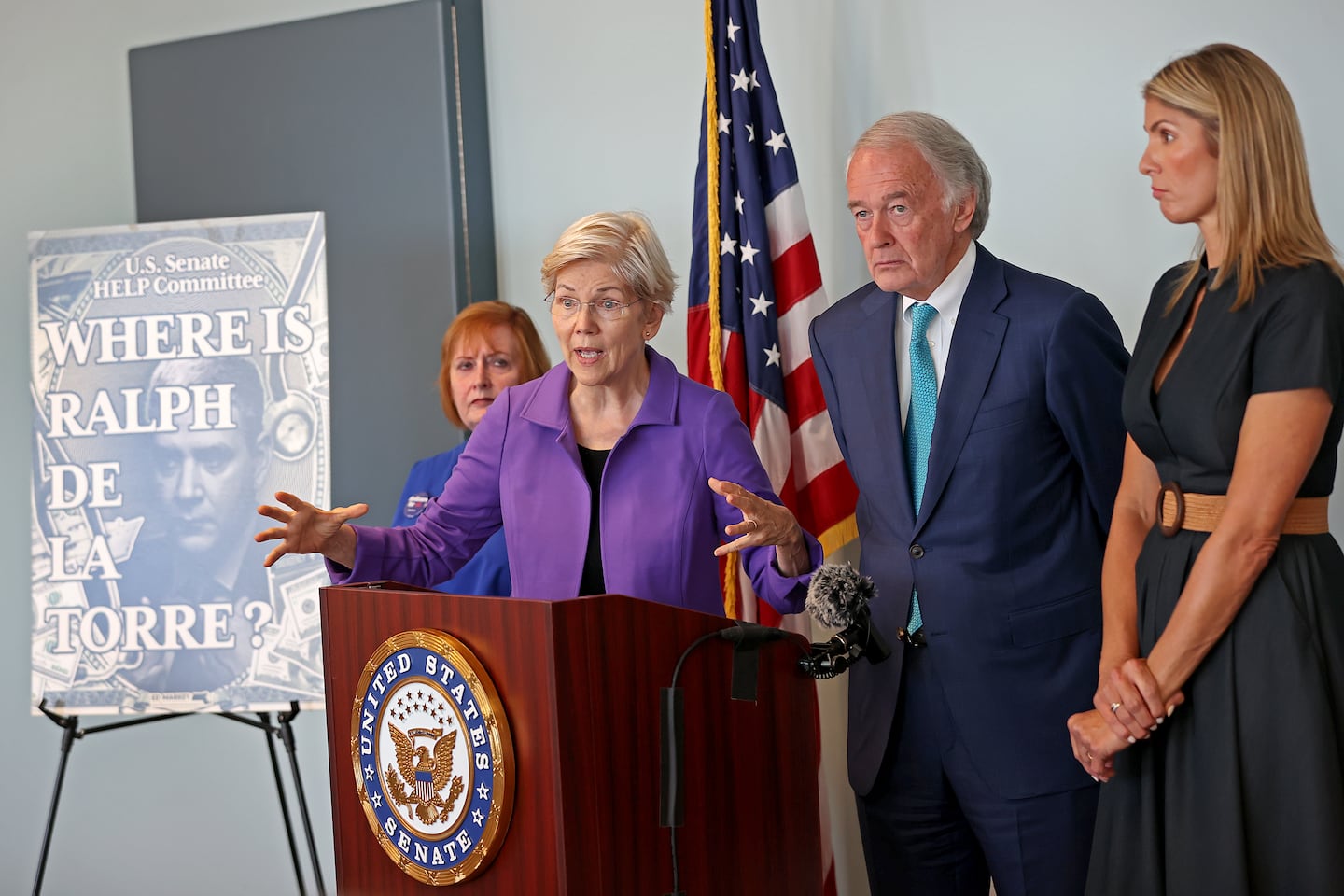

“We still have a long road ahead,” said Senator Edward Markey, who cosponsored a bill that would prohibit private equity firms from stripping assets from health providers. “Unfortunately, this is a slow moving process,” he said.

Markey warned the incoming Trump administration, with its strong ties to Wall Street, could block efforts to regulate those private interests.

State Senator Cindy Friedman, an Arlington Democrat who cochairs the Health Care Financing Committee on Beacon Hill, said she’s similarly frustrated by how long it’s taking to reconcile separate House and Senate health care bills to rein in private equity.

Both she and Representative John Lawn, who are negotiating in a conference committee, said it’s still possible a consensus bill with some limits on private equity could emerge by year-end. Friedman conceded, however, that despite broad support for the measures, it’s more likely consideration of the bills will be delayed until next year.

“I want to do this faster,” she said. “It is hugely complicated. In Massachusetts, people get very nervous about what happens to the health care system because of the importance it plays in our state.”

With the dissolution of Steward, there are no longer any hospitals in Massachusetts owned by private equity firms. But buyout firms continue to own and run at least a dozen nursing homes, rehab facilities, behavioral health clinics, and specialty doctors groups in the state, according to the state Health Policy Commission.

Kinderhook merged Stewardship with a smaller physicians group it operated in Tennessee and North Carolina into a new affiliate called Revere Medical. Its chief executive, Benson Sloan, who lives in Nashville, attended a Massachusetts Health Policy Commission hearing in Boston last month. He pledged that, unlike Steward, his organization would file financial reports with the state and seek to build trust with regulators.

Markey remains skeptical. He noted the organization has retained former Steward executives, including Joseph Weinstein, the former president of Stewardship, who is now Revere’s chief medical officer.

A spokesperson for Revere didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Health care reformers say the anxiety over another private equity player in Massachusetts underscores the need for new laws in the post-Steward era enabling regulators to block buyout firms and their practice.

“Evidence that private equity is harming the health care system at large is pretty strong now,” said Don Berwick, senior fellow at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and former administrator of the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. He cited studies showing health care quality deteriorates at providers owned by private equity.

State and federal lawmakers said their bills had stalled for a variety of reasons, ranging from competing priorities to legislative inertia to intense lobbying by financial interests with ample resources.

Critics said Congress and most states, including Massachusetts, have failed to follow through and block the abuses by operators such as Steward, which sold its hospitals’ property to a real estate investment trust before issuing a giant dividend payout to ex-CEO Ralph de la Torre and other shareholders. That sale left hospitals on the hook for monthly rent payments they struggled to afford.

Federal agents are investigating de la Torre over Steward’s overseas business and allegations of potential fraud and embezzlement in the US, the Globe has reported.

Hours after Steward filed for bankruptcy on May 6, putting its hospitals in the state at risk, Massachusetts House Speaker Ron Mariano promised legislative action to prevent other buyout firms from adopting the playbook deployed by the chain and its private equity backer, Cerberus Capital Management, which owned Steward from 2010 to 2020.

“It is the Legislature’s responsibility to ensure that what happened with Steward Health Care never happens again,” Mariano said in a statement on May 6. He declined to discuss the status of the effort for this story.

And a month before, at a US Senate “field hearing” in the Massachusetts State House, Markey and Senator Elizabeth Warren trumpeted bills to prevent buyout firms from snapping up and extracting wealth from health care assets.

“Private equity should not be allowed to loot one business after another,” Warren said.

Warren has filed two bills, one that would restrict how much money firms can extract from their portfolio companies, and a second that would create stiff criminal penalties for executives whose draining of resources from health care providers result in patients’ deaths.

In the state Legislature, measures targeting private equity also vary. One would bar owners from selling hospital property to real estate investment trusts, as Steward did, while another would require hospitals to maintain enough cash reserves to operate for a year if their owners pull up stakes.

Both the federal and state bills stop short of outright banning health care buyouts by investors. Some officials in Massachusetts, including Secretary of Health and Human Services Kate Walsh, caution against lumping all private equity firms into the Steward camp. Citing the success of the state’s biopharma industry, fueled by venture capital, they say private investment can boost cash-starved health care organizations.

Berwick said the goal of policy makers should be to stop profit-minded investors from “controlling the delivery of care.” Decisions on how many patients doctors see and how much time they spend with them, for example, should be made by doctors, not investors, he said.

“It’s disappointing if these bills are not moving forward,” he said.

Robert Weisman can be reached at [email protected].